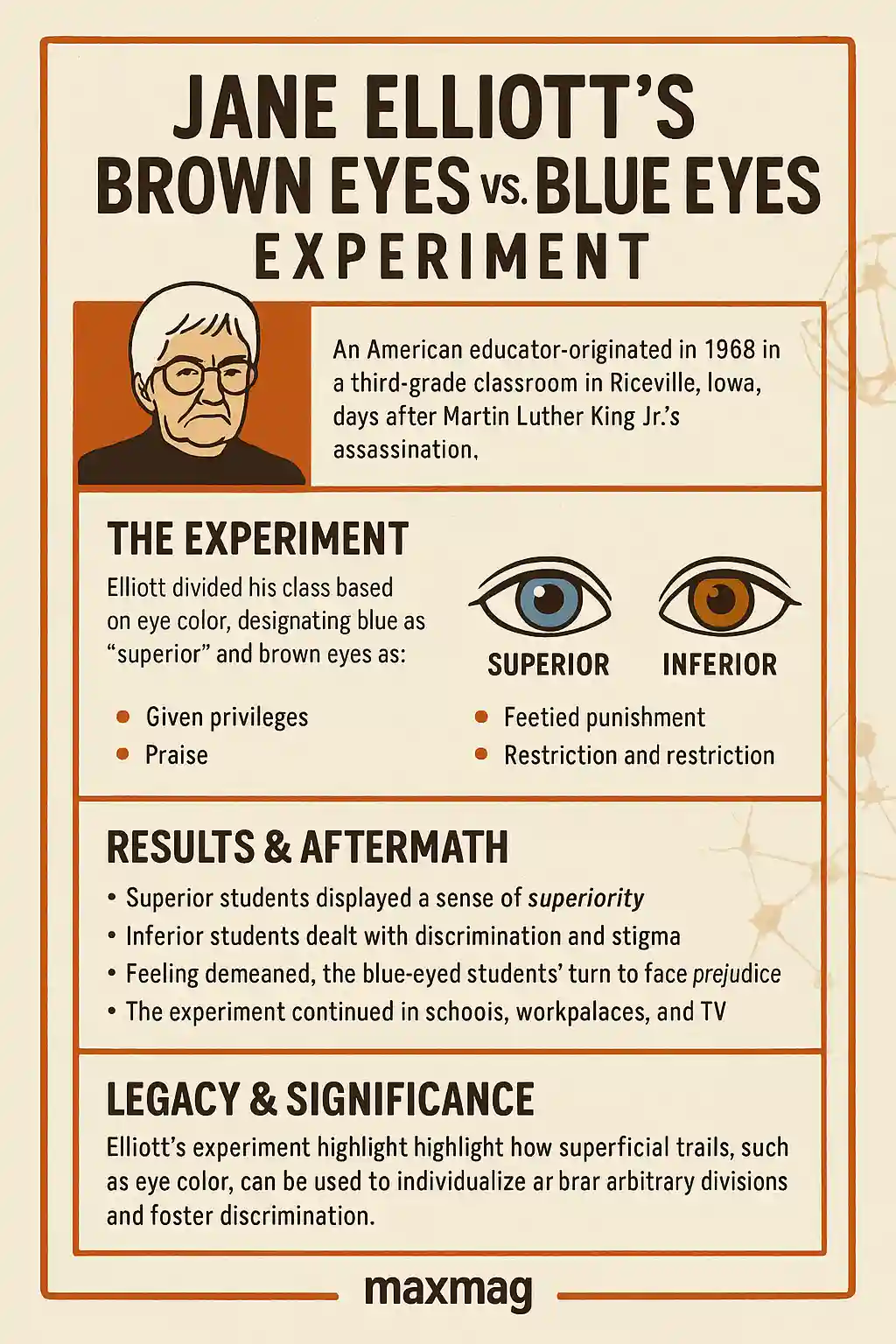

In April 1968, the landscape of American education—and anti-racism teaching—changed forever. Following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a small-town teacher named Jane Elliott launched what would become globally known as the blue eyes brown eyes anti-racism experiment. Her goal wasn’t to lecture her students about prejudice, but to make them feel it. What unfolded in her classroom sparked national dialogue, inspired decades of diversity training, and ignited an ongoing ethical debate.

But what exactly happened in that Iowa classroom? Why does it still provoke admiration and criticism in equal measure? And what can we learn today from this controversial yet influential experiment?

The Origins: A Teacher’s Response to Tragedy

Jane Elliott, like millions of Americans, was devastated by the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. As an educator and the mother of young children, she was grappling with how to address the event with her students in a meaningful way. Her solution? She would simulate the arbitrary nature of racism by dividing her class based on a completely superficial trait: eye color.

On that first day, Elliott told her class that blue-eyed students were inferior to brown-eyed ones. She cited pseudoscientific justifications—”brown-eyed people have more melanin”—and enforced immediate structural bias. Brown-eyed children were given longer recesses, sat at the front of the class, and were praised more often. Blue-eyed children, by contrast, were restricted from using the water fountain and were told they were not as smart or trustworthy.

What shocked Elliott most was how quickly the children adopted their new roles. Blue-eyed kids became timid, insecure, and made more mistakes in their lessons. Brown-eyed students gained confidence and were quick to taunt their “lesser” classmates. The following day, Elliott reversed the roles—and the same behavioral patterns emerged, just in reverse.

The exercise laid bare the psychology of discrimination. Within hours, children began internalizing the labels they were given. Performance, friendships, and self-worth all shifted under the weight of false beliefs.

Documenting Discrimination: The Media Response

What started as a classroom lesson soon gained national attention. Jane Elliott’s experiment became a subject of deep public interest, especially after her students wrote essays describing their feelings during the activity. These essays were published in the local Riceville Recorder and caught the eye of larger media outlets. The story quickly spread beyond Iowa.

In 1970, ABC aired a documentary titled The Eye of the Storm, which showcased the original footage from Elliott’s classroom. It provided a raw and unfiltered view of how children navigated bias imposed by authority. The footage was emotionally intense—students cried, became angry, and showed how powerful group dynamics can be.

Fifteen years later, PBS released A Class Divided, revisiting the same students as young adults. They reflected on how the blue eyes brown eyes anti-racism experiment had shaped their perceptions of justice, fairness, and empathy.

To this day, these documentaries are used in educational programs and are available for viewing through trusted sources like PBS Frontline, which provides critical historical and emotional context for the experiment.

From Children to Corporations: A National Training Tool

Elliott’s experiment didn’t end in her third-grade classroom. As public interest grew, she began adapting the exercise for adults—teaching in universities, government agencies, and major corporations. Her sessions were bold and, at times, confrontational. Adults who participated were often reduced to tears as they experienced prejudice firsthand.

Elliott facilitated these workshops with employees of General Electric, AT&T, IBM, and even within the U.S. Department of Education. Many attendees described the experience as transformative, although not necessarily pleasant. For some, it was the first time they were made to feel what it’s like to be dismissed or stereotyped based on something beyond their control.

The experiment was lauded for its immersive quality and criticized for its emotional strain. Nevertheless, it inspired a wave of experiential learning programs in diversity and inclusion fields. Even as modern training programs evolve, Elliott’s model remains a touchstone for how to address implicit bias in real time.

In a modern context, her work aligns with studies on implicit bias in workplace behavior as covered by the Harvard Business Review. These studies affirm that systemic issues can’t be resolved through policy alone—personal transformation is often necessary.

Ethical Dilemmas and Long-Term Effects

Despite its educational power, the blue eyes brown eyes anti-racism experiment has not escaped criticism. Ethical concerns have shadowed the exercise since its inception. Key points of contention include:

-

Psychological harm: Some participants, especially adults, reported lasting emotional discomfort.

-

Lack of consent: Elliott often surprised participants with the exercise, which raised questions about informed participation.

-

Reinforcement of stereotypes: Critics argue that putting people into oppressor/oppressed roles could backfire or reinforce harmful behavior if not properly debriefed.

While Elliott has defended her approach as a “necessary discomfort,” some psychologists argue that trauma—however brief—should not be a method of instruction. Yet others insist that this temporary discomfort reveals unconscious prejudice more powerfully than lectures or books ever could.

Even studies from Bard College and Stanford University that questioned long-term behavioral change conceded the experiment’s short-term effectiveness in raising awareness. The ethical debate thus hinges not on whether the method works, but how it should be used—and who should administer it.

A Pioneer in Anti-Racism Education

Jane Elliott’s legacy is hard to overstate. She has received awards from the National Education Association and numerous civil rights organizations. Yet she remains a polarizing figure. In interviews, she often points out how little has changed since 1968. “Racism is alive,” she has said bluntly. “We’ve just gotten better at hiding it.”

Her goal has never been comfort. Instead, she strives for clarity. In her view, real education begins when people become uncomfortable enough to ask hard questions about their own behavior.

The blue eyes brown eyes anti-racism experiment forces people to confront those hidden assumptions. It reveals how easily systems of privilege and discrimination can be created—and how quickly people will play their roles in those systems.

Broader Implications in Education and Society

At its core, the experiment serves as a metaphor for the artificial construction of race and class. By arbitrarily assigning value based on eye color, Elliott mimicked how society grants unearned advantages to some and imposes penalties on others.

The relevance of this metaphor has only grown. In modern classrooms, where students come from increasingly diverse backgrounds, the need for culturally responsive teaching is urgent. And in workplaces struggling to embrace equity, the lessons of the experiment resonate deeply.

Whether used in anti-bias workshops or university seminars, Elliott’s work continues to provoke thought and inspire change. The growing availability of virtual reality simulations and role-play education builds upon her model—proving that immersive learning still holds power in the digital age.

Why This Experiment Still Resonates Today

More than five decades after its inception, the blue eyes brown eyes anti-racism experiment remains one of the most visceral demonstrations of bias ever attempted in an educational setting. Its power lies in its simplicity: create a divide, assign privilege, and observe.

The results speak volumes. People adapt quickly to the power they’re given. They also internalize inferiority just as fast. This insight remains crucial for understanding how prejudice takes root and why structural change requires more than just laws—it demands emotional awareness.

As we navigate conversations about racial equity, social justice, and educational reform, Elliott’s experiment serves as both a warning and a guidepost. It reminds us how easily inequality can emerge—and how deliberately we must work to dismantle it.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the blue eyes brown eyes anti-racism experiment?

It’s a social simulation created by educator Jane Elliott in 1968 to demonstrate the impact of discrimination. Participants are divided by eye color and treated differently to mimic racial prejudice.

Was the experiment successful?

It is widely regarded as effective in provoking empathy and awareness, particularly in the short term. However, debates continue about its long-term effects and ethical use.

Can this experiment still be used in classrooms?

While many educators draw inspiration from it, direct replication—especially with minors—is rare today due to ethical concerns. Adapted models are sometimes used in diversity training with adult consent.

Who has used this method?

Jane Elliott has led sessions for government agencies, corporations like IBM, and educators. Her techniques have inspired other forms of interactive anti-bias training.

Where can I learn more?

Watch A Class Divided on PBS Frontline or read Harvard Business Review on inclusive workplace strategies.