In the heart of ancient Athens stands a structure that has quietly defied time itself—a monument that fuses scientific precision with architectural grace. The Tower of the Winds architecture represents one of the most remarkable examples of ancient engineering, where functionality and beauty intersect in service to the civic good. Designed during the Hellenistic period and standing resilient through Roman occupation, Christian conversion, and modern rediscovery, the Tower of the Winds is more than a marble relic—it’s a symbol of humanity’s early efforts to understand and regulate time, wind, and space.

This article offers a comprehensive look at the architecture, scientific mechanisms, symbolic design, and enduring influence of this 2,000-year-old structure—revealing why it still commands global admiration today.

The Origins of the Tower of the Winds

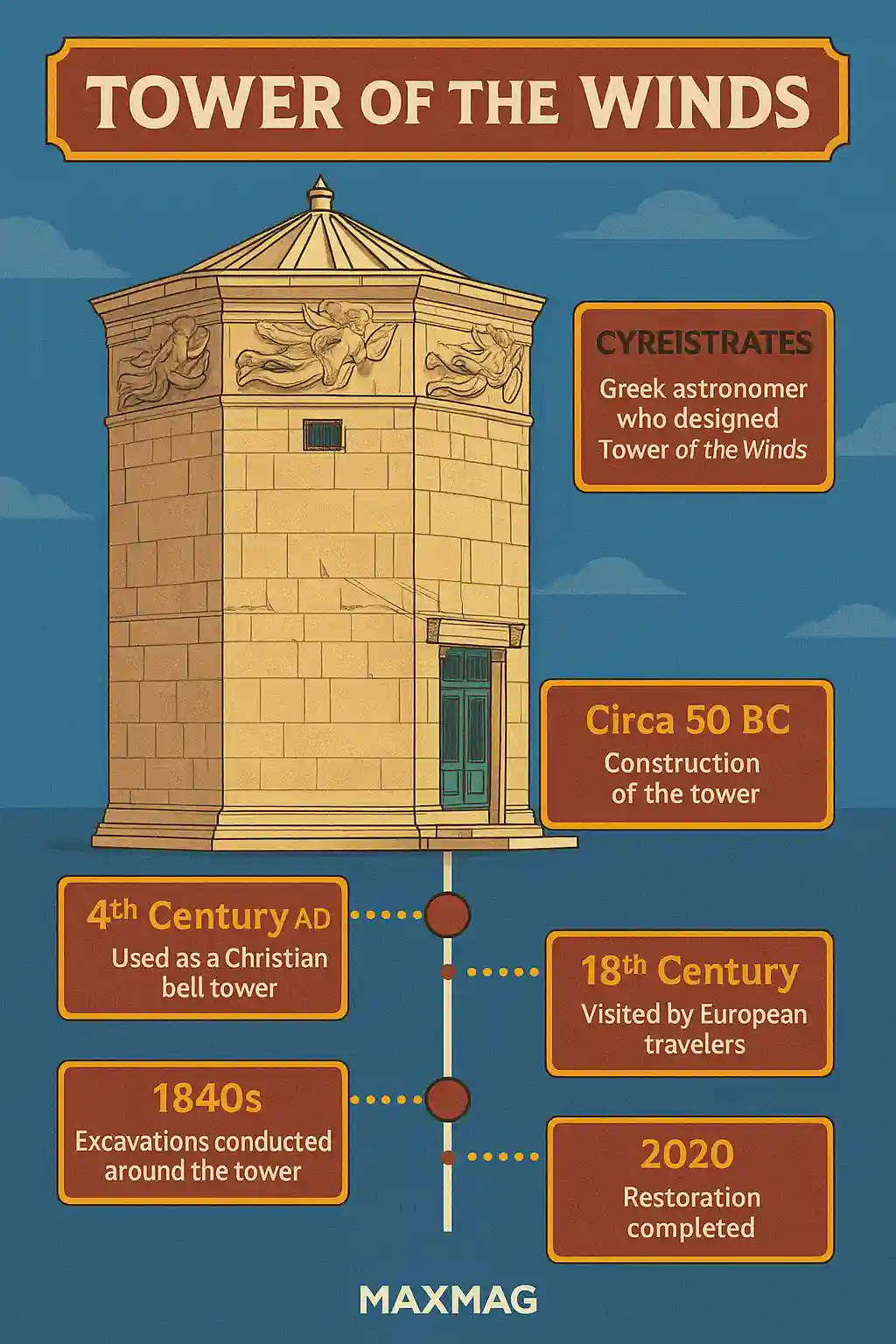

The Tower of the Winds, or Horologion of Andronikos Kyrrhestes, was built in the 1st century BCE by Andronicus of Cyrrhus—a Greek astronomer and engineer. Situated in the Roman Agora of Athens, the tower is octagonal in shape, constructed from pristine Pentelic marble, and measures about 12 meters (40 feet) in height and nearly 8 meters in diameter.

Its purpose was both practical and symbolic: to tell the time (via sundials and a water clock), to indicate wind direction (via a weather vane), and to symbolize the harmony between human civilization and natural forces. The tower essentially functioned as a public clock tower, centuries before such a concept became common in medieval Europe.

Why the Octagonal Design Matters

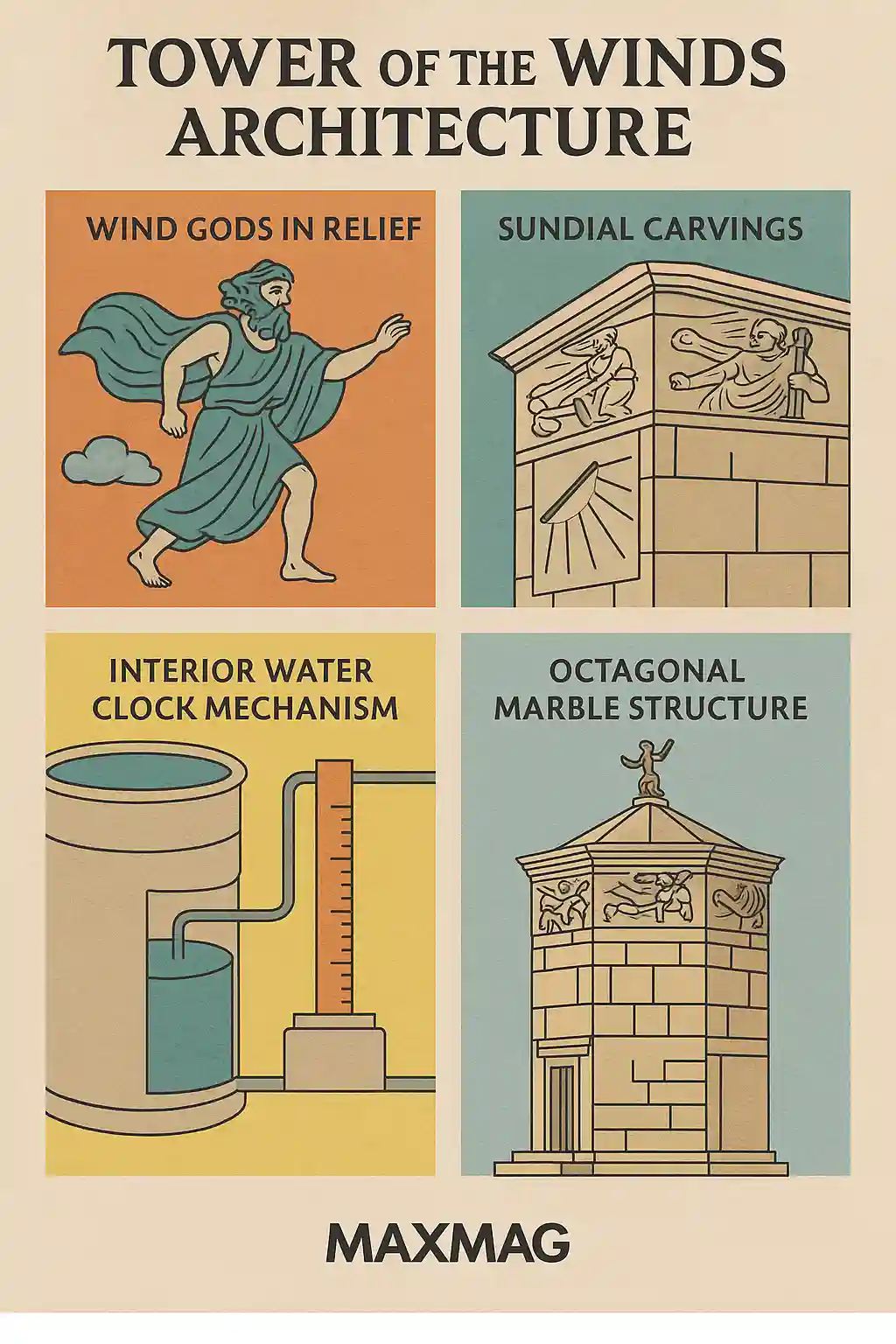

The decision to design the tower with eight sides was not arbitrary. Each face of the octagon represents one of the eight principal wind directions as defined in Greek meteorology: Boreas (north), Kaikias (northeast), Apeliotes (east), Eurus (southeast), Notos (south), Lips (southwest), Zephyrus (west), and Skiron (northwest).

Above each face, carved in high relief, is the corresponding wind god (Anemos), each depicted in motion, bearing attributes to symbolize their effect on the world—snow, rain, fire, or sailing winds. These reliefs combine mythology with meteorological function, creating a fusion that defines Tower of the Winds architecture: beauty, science, and symbolism, all carved in stone.

Scientific Innovation: Sundials, Weather Vane, and Water Clock

The Tower of the Winds is not merely a decorative structure—it is a scientific instrument embedded in architecture. Its three main functional components included:

1. Exterior Sundials

Each side of the tower features a shallow, carved sundial that could tell time based on the shadow cast by a horizontal gnomon. These sundials were carefully angled to account for the sun’s position during different times of the day and year.

2. Interior Water Clock (Clepsydra)

Inside the tower, a sophisticated water clock allowed Athenians to keep time even on cloudy days or during the night. Water flowed from a tank (likely fed by a nearby spring or cistern), turning gears that moved a vertical pointer along a column marked with hour lines. This mechanism would have been visible through a niche or open panel, allowing citizens to check the time at any moment.

3. Weather Vane

Atop the conical roof once stood a bronze Triton, a mythological sea deity holding a rod. This acted as a weather vane, turning with the wind and pointing to the corresponding wind god below. The combination of wind direction, time of day, and architectural symbolism makes the Tower of the Winds one of the earliest known examples of a multi-functional scientific monument.

Architectural Details and Construction Techniques

Crafted from Pentelic marble, the same material used for the Parthenon, the Tower was both durable and visually striking. Its octagonal plan not only symbolized completeness and balance but allowed each wind god to be equidistant and directionally accurate.

Key architectural features include:

-

Fluted pilasters between each face, adding verticality and grace

-

Entablature bands separating wind carvings from the sundials

-

A conical roof supported by an interior frieze

-

Internal spiral staircase providing access to the water clock and roof

No mortar was used—each marble block was precision-cut and stacked with remarkable skill, a hallmark of advanced Hellenistic engineering. Drainage channels were carved into the base to prevent water damage, ensuring longevity.

Today, the American School of Classical Studies at Athens maintains detailed architectural surveys and 3D renderings of the site, supporting ongoing conservation efforts.

Public and Religious Functions Through Time

Originally, the tower stood near several important public buildings—stoas, administrative offices, and law courts. It functioned not just as a tool for individuals, but as a civic device—standardizing time and natural observations for use in legal, commercial, and ritual contexts.

As Athens transitioned through Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman control, the Tower was repurposed. In the early Christian era, it became a bell tower for the Church of St. Anastasia. During the Ottoman occupation, it was used by dervishes as a place of whirling dance and prayer. Each new culture found a purpose for it—yet none altered its core form. This continuity is a testament to the enduring utility of Tower of the Winds architecture.

Symbolism of the Winds and Their Deities

Each wind carved on the tower bears more than artistic merit—they serve as climatic codices, warning or guiding citizens. Here are the eight Anemoi and their traditional attributes:

-

Boreas (North): Fierce and icy, bringing winter snow

-

Kaikias (NE): Cold and dusty, associated with storms

-

Apeliotes (E): Mild and nurturing, linked to agriculture

-

Eurus (SE): Unpredictable and stormy

-

Notus (South): Humid, bringing summer rain

-

Lips (SW): Warm and useful for sea travel

-

Zephyrus (West): Gentle breeze, symbol of spring

-

Skiron (NW): Dry wind associated with health and purity

These anthropomorphic figures embody natural forces and allowed ancient Greeks to read and respond to weather shifts intuitively—transforming Tower of the Winds architecture into a public weather guide centuries ahead of modern meteorology.

Influence on Later Cultures and Structures

The Tower’s influence reached far beyond Athens. Its blend of artistic narrative and functional design inspired architectural thinking throughout the Mediterranean and beyond:

-

Islamic architecture incorporated similar observational towers in Isfahan and Samarkand.

-

Roman horologia in cities like Pompeii featured sundials that drew on Athenian design.

-

Renaissance architects, particularly Palladio, referenced the Tower as an ideal synthesis of form and function.

-

Clock towers in medieval Italy, such as in Venice and Florence, owe part of their legacy to the Tower’s civic role.

In many ways, it served as a prototype for urban architecture that serves both informational and symbolic purposes.

The Tower as a Precursor to Smart Architecture

In an era increasingly focused on smart cities and intelligent urban design, the Tower of the Winds offers a compelling ancient precedent. It was a multimodal interface:

-

Displaying real-time environmental data (wind, sun)

-

Offering analog time via sundials and clepsydra

-

Visually reinforcing civic identity and divine order

Today’s city planners can draw inspiration from this early “data hub”—a monument designed not just to last, but to serve, educate, and integrate information in accessible form.

Rediscovery and Preservation

The Tower fell into ruin during the 18th century and was buried up to its roof. It was fully excavated in the 19th century during systematic studies of Athens’ Roman Agora. Restoration efforts in the 20th and 21st centuries have focused on cleaning, structural reinforcement, and visitor safety.

Recent technological advances such as laser scanning, 3D modeling, and environmental simulation have further deepened our understanding of how the sundials and water clock functioned. The Greek Ministry of Culture collaborates with academic institutions like the University of Athens and Harvard University to digitally reconstruct the tower’s original state.

Visitor Experience Today

Modern visitors to Athens can access the tower through the Roman Agora site. While the roof vane is missing, the carvings, sundials, and internal structure remain remarkably intact. Interpretive signage, augmented reality apps, and online guides provide a rich understanding of its architecture and mechanics.

You can even simulate the original sundial readings and water clock mechanisms through interactive models provided by The Met, bridging the ancient and the digital worlds.

Conclusion: A Monument Beyond Time

The Tower of the Winds architecture is more than a marvel of ancient craftsmanship—it is a lasting example of how science and civic life can coexist in one structure. It tells us not only about time, wind, and weather, but about how ancient societies designed their world with purpose. Through art, mathematics, mythology, and urban planning, the tower became a beacon of intelligence and cultural memory—an achievement unmatched for centuries.

As modern architecture seeks to be smarter, greener, and more human-centered, the Tower of the Winds reminds us that these ideals are not new—they are simply the rediscovery of ancient genius.

❓FAQ

Q1: What is the Tower of the Winds?

An ancient Athenian monument built in the 1st century BCE that functioned as a sundial, water clock, and weather vane.

Q2: Who built the Tower of the Winds?

It was designed by Andronicus of Cyrrhus, a Greek astronomer and engineer from Syria.

Q3: Why does the tower have eight sides?

Each side represents a cardinal or intercardinal wind, with a relief of its associated wind deity.

Q4: How did the water clock work?

Water flowed through a mechanism that moved a float and vertical pointer, marking the passage of hours.

Q5: What materials were used to build it?

The structure was made from Pentelic marble, prized for its durability and elegance.

Q6: What was its role in ancient Athens?

It served as a civic tool for regulating time and understanding weather—accessible to citizens, merchants, and officials.

Q7: Can I visit the Tower of the Winds today?

Yes, it’s open to the public as part of the Roman Agora archaeological site in Athens.

Q8: How does it influence modern design?

Its blend of aesthetics and function serves as an early model for today’s smart and sustainable architecture.