In the myth-shrouded ruins of ancient Crete, where sacred rites and myths converged, a legendary figure once haunted the human imagination: the Minotaur. A monstrous fusion of man and bull, imprisoned within the winding corridors of a labyrinth, this creature has remained one of the most captivating—and misunderstood—symbols of classical mythology.

But beneath the surface horror lies something deeper. The Minotaur symbolism meaning stretches far beyond myth, speaking to the hidden corners of our psychology, the dark urges society buries, and the transformative journey from chaos to clarity. By examining its mythological roots, cultural resonance, artistic legacy, and modern relevance, we unlock a profound metaphor still pulsing beneath the skin of civilization.

The Myth of the Minotaur: Where it All Began

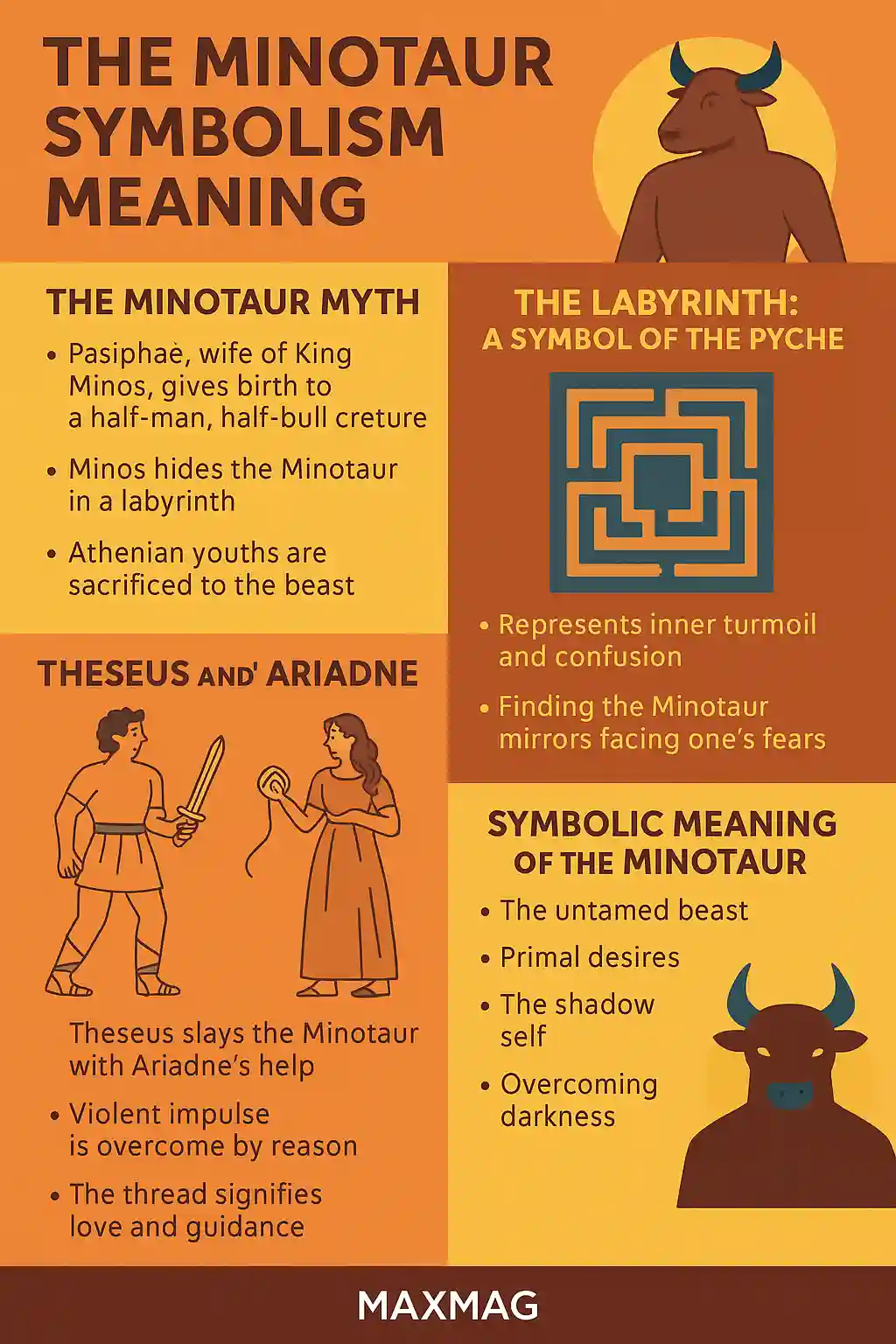

To understand the Minotaur symbolism meaning, we must return to its mythic origin. According to Greek legend, King Minos of Crete was granted a glorious white bull by Poseidon as a token of divine favor. But Minos, captivated by the bull’s beauty, defied the god by refusing to sacrifice it. In vengeance, Poseidon cursed Minos’s queen, Pasiphaë, with an unnatural passion for the animal. The outcome was a grotesque birth: the Minotaur—part man, part bull.

Ashamed and afraid, Minos concealed the beast inside a labyrinth designed by Daedalus. It wasn’t merely a prison. It was a symbol of denial, of avoidance, and of the ancient pattern of hiding what we cannot accept. The Minotaur’s very existence revealed a clash between divinity and human arrogance, desire and suppression.

This myth, preserved in countless versions across ancient Greek literature and Cretan oral traditions, formed the foundation for a creature who, like Medusa or the Hydra, would evolve far beyond his original tale.

The Labyrinth as Inner Landscape

The labyrinth is not just a setting—it’s a metaphor. Within its walls, we find the psychological terrain of fear, guilt, repression, and mystery. While many ancient myths were straightforward moral tales, the Minotaur’s myth invites interpretation.

Jungian psychologists, for instance, have long viewed the labyrinth as symbolic of the unconscious mind—a spiraling descent into the self where one must face their most dangerous truths. In that sense, the Minotaur symbolism meaning isn’t externalized horror. It’s the “shadow” archetype—the animal instinct, the emotional chaos, the buried trauma waiting to be confronted.

The figure of the Minotaur becomes what we fear in ourselves. His head, bullish and instinct-driven, contrasts with the human body he possesses—reminding us that reason and impulse coexist in uneasy harmony. As the American Psychological Association notes, myths often encode psychological truths that remain relevant even in our data-driven world (apa.org).

Blood Price: The Athenian Tribute and Political Allegory

Following the death of Minos’s son Androgeos—who was either slain or sabotaged during games in Athens—Minos imposed a cruel judgment. Every nine years, fourteen Athenian youths (seven boys and seven girls) were to be delivered to the labyrinth as tribute. Their fate: to be devoured by the Minotaur.

This recurring sacrifice wasn’t just divine punishment. It was a symbol of submission, of generational guilt, and of power enforced through ritual terror. The people of Athens were forced to surrender their most promising youth—perhaps a metaphor for the way unjust systems consume future potential.

Some scholars argue this part of the myth may echo real historical tensions between Crete and mainland Greece during the Bronze Age. Others see it as a commentary on the cyclical nature of violence and how fear can be institutionalized.

Either way, the Minotaur became not only a monster but a mechanism for maintaining control through fear—much like the modern ways societies uphold silence or oppression under the guise of order.

Theseus: Heroism, Strategy, and the Thread of Liberation

Theseus’s arrival marks the pivotal moment in the myth. The young Athenian prince, determined to end the sacrifice once and for all, volunteers to join the doomed youths. Yet he doesn’t rely solely on strength—he relies on help and wisdom.

Ariadne, daughter of Minos, gives him a thread to trace his steps back through the labyrinth. With this tool and his courage, Theseus confronts and slays the Minotaur, liberating the Athenians and himself from the cycle of fear.

This thread, often overlooked in favor of the slaying, is rich in symbolism. It represents intuition, guidance, emotional intelligence—typically coded as feminine virtues. Without Ariadne, Theseus would have perished. In today’s context, this might reflect how confronting our inner demons often requires insight, not aggression.

The Minotaur symbolism meaning here shifts again: the creature becomes not simply a beast to conquer, but a trial to endure—requiring help, strategy, and inner alignment to overcome.

The Bull as Ancient Sacred Animal

Before the Greeks ever told stories of Minos or Theseus, bulls were revered across the Mediterranean. In Minoan Crete, bulls appeared in religious frescoes, such as the famous bull-leaping scenes at Knossos. Bulls represented virility, strength, and the regenerative cycle of nature.

The Minotaur, then, fuses this ancient reverence with modern horror. He is the dark shadow of what was once divine—twisted by taboo, hidden by shame, and transformed into fear. That tension between sacred and profane adds depth to the Minotaur symbolism meaning, particularly in the context of societies that struggle to reconcile instinct with ideology.

Artistic Rebirth: From Vase to Canvas

The Minotaur’s transition from myth to modernity occurred gradually. In ancient pottery, such as Athenian black-figure vases, artists depicted Theseus battling the creature—an emblem of rational heroism. But it was in the 20th century that the Minotaur truly transformed.

Pablo Picasso reimagined the Minotaur in deeply personal ways. During Spain’s civil war, he portrayed the beast as a tragic, blinded wanderer. In etchings like Minotauromachy and Blind Minotaur Led by a Little Girl, the creature becomes a symbol of war, masculinity in crisis, and inner darkness.

Picasso’s Minotaur is not a villain. He is a reflection of human pain, caught between civilization and primal instinct. His works, preserved in institutions like the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, offer a haunting reinterpretation that reframes the myth for the modern world (moma.org).

The Minotaur in Contemporary Culture

Today, the Minotaur appears in novels, films, video games, and even therapy rooms. Writers like Jorge Luis Borges gave the creature a voice, framing him not as monstrous but misunderstood. Films like Pan’s Labyrinth play on the motif of mazes, creatures, and personal trials.

In video games, the Minotaur often appears as a “boss” to defeat—visually powerful, rooted in labyrinthine settings, and always the final test. Even educational institutions, like the Smithsonian Magazine, have explored the creature’s symbolic evolution and artistic legacy in Western culture (smithsonianmag.com).

In psychology, the Minotaur is often used as a metaphor for:

-

The repressed child within, wounded and angry

-

Addiction or compulsion, that feeds in the darkness

-

Societal fears, such as violence, shame, or isolation

These interpretations highlight the enduring relevance of the Minotaur symbolism meaning in personal growth, trauma recovery, and social critique.

Labyrinths in the Real World

Interestingly, labyrinths exist far beyond metaphor. From medieval cathedrals to modern therapeutic gardens, labyrinths have been constructed as meditative tools. Unlike mazes, which have dead ends and confusion, labyrinths typically have one path in and one path out.

Walking a labyrinth today is considered a spiritual act—used in trauma therapy, grief rituals, and reflection practices. The Minotaur, then, becomes not an enemy but a presence at the center of one’s own spiritual journey.

Modern therapeutic use of labyrinths is recognized by mental health professionals as a grounding and healing method—backed by organizations like the Cleveland Clinic (clevelandclinic.org).

The Minotaur as a Mirror

Ultimately, the minotaur symbolism meaning reveals less about a mythical beast and more about us. He is:

-

The part of ourselves we deny

-

The rage we suppress

-

The hunger we fear to name

-

The child abandoned by power

And when we slay him, as Theseus did, we don’t destroy him—we integrate him. We recognize our darkness and choose not to be ruled by it. That’s why the myth endures. We’re all walking the labyrinth in some way.

FAQ

1. What is the deeper symbolism of the Minotaur?

The Minotaur represents our primal instincts, repressed trauma, and the fear of confronting hidden aspects of ourselves.

2. Why was the Minotaur placed in a labyrinth?

The labyrinth symbolizes the mind’s complexity. The creature was hidden there out of shame and fear, making it both prison and metaphor.

3. How is Ariadne’s thread interpreted today?

It’s seen as guidance—intuition, love, or clarity—that helps navigate confusion and emerge from psychological darkness.

4. What does the Athenian tribute represent?

The tribute reflects cycles of guilt, punishment, and submission—especially how societies sacrifice youth to uphold flawed systems.

5. How do modern artists interpret the Minotaur?

Artists like Picasso portray him as tragic, wounded, and emotionally complex—more human than monster.

6. How is the Minotaur relevant in therapy or psychology?

The Minotaur is often a metaphor for facing one’s inner fears and traumas, especially in Jungian or shadow-work contexts.