Maria Montessori was more than an educator—she was a visionary who transformed how the world thinks about learning, human potential, and social justice. In an era when children were often seen as empty vessels to be filled with knowledge, Montessori championed a radical idea: that every child carries within them the seed of a fully realized, independent, and capable adult.

Her educational method wasn’t just a new teaching technique—it was a philosophy, a movement, and a rebellion against the rigidity of the traditional school system. Maria Montessori’s influence stretches far beyond classrooms. It touches parenting styles, early childhood development, social policy, and even the design of workspaces and therapeutic environments.

A Defiant Start in a Man’s World

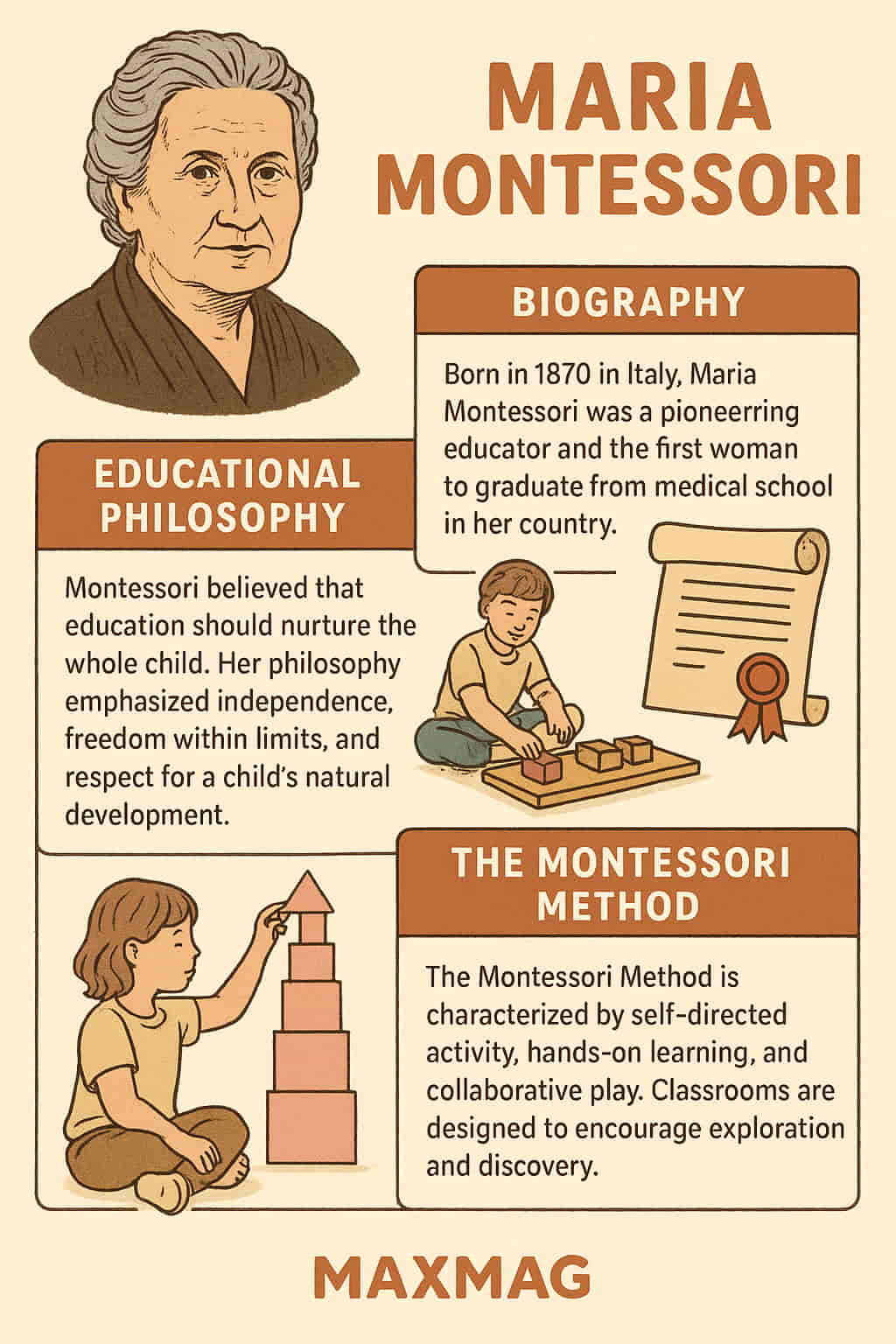

Born in 1870 in the small Italian town of Chiaravalle, Maria Montessori was raised in a country where education for girls was still controversial. From a young age, she exhibited a fierce intellect and determination that defied societal expectations. Despite being discouraged by teachers and peers, she enrolled in the University of Rome to study medicine, becoming one of Italy’s first female physicians in 1896.

Her medical training gave her a scientific lens through which to observe human behavior, and her work with children in asylums—many of whom had been labeled unteachable—triggered a profound realization: these children didn’t lack intelligence; they lacked opportunity, stimulation, and respect.

Montessori began designing learning tools—tactile, hands-on materials that engaged the senses and helped children interact with the world around them. Her scientific and humanistic approach would form the foundation of what would later be called the Montessori Method.

The First Casa dei Bambini

In 1907, in Rome’s poverty-stricken San Lorenzo district, Maria Montessori opened the first “Casa dei Bambini” (Children’s House). The children were from working-class families, many with limited access to education. Montessori believed that intelligence was not fixed and that even the poorest children could achieve remarkable development if given the right environment.

Rather than traditional classroom desks, she used child-sized furniture and carefully designed materials that allowed the children to explore independently. The room was orderly, beautiful, and filled with purposeful activity. There were no lectures, no punishments, no rote memorization. Yet within weeks, observers noted remarkable changes: the children became more focused, independent, and joyful.

This success led to international attention and the rapid spread of her methods around Europe and the world.

For historical context on early Montessori classrooms, explore Montessori Centenary’s archives.

Montessori’s Core Beliefs and Practices

Maria Montessori believed that education should be a natural, self-directed process, rather than a mechanical delivery of facts. At the heart of her approach were several key principles:

-

Respect for the child: Montessori believed that children deserve the same dignity and autonomy as adults.

-

Absorbent mind: Especially from birth to age six, children have an incredible capacity to absorb information from their surroundings without direct instruction.

-

Sensitive periods: Certain phases in childhood are optimal for learning specific skills like language, order, or social behavior.

-

Prepared environment: Montessori classrooms are intentionally designed to promote exploration and self-correction.

-

Freedom within limits: Children are free to choose activities, but within a framework that guides development.

In this philosophy, learning is not a top-down activity; it is collaborative and internally motivated. The teacher, known as a “guide,” steps back and allows the child to take ownership of their education.

H2: Maria Montessori’s Global Educational Impact

The name Maria Montessori is now associated with over 25,000 schools in more than 140 countries. But her global reach didn’t happen overnight. She tirelessly traveled, wrote books, and trained educators across cultures, adapting her philosophy to different communities without compromising its core values.

In the United States, Montessori’s ideas gained popularity in the early 20th century, with support from leading thinkers like Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Edison. Although the movement waned due to misunderstandings and lack of trained teachers, it resurged in the 1960s thanks to dedicated educators and parents seeking alternatives to conventional education.

Today, her method is used in private schools, public school programs, and even refugee camps. From preschool to adolescence, Montessori education fosters independent thinking, emotional intelligence, and real-world skills.

See how public Montessori schools are growing across the U.S. in this NPR feature.

Montessori and the Modern Mind

In an age where screen time, standardized testing, and anxiety are rising, Maria Montessori’s approach feels more relevant than ever. She emphasized slow, mindful engagement with the physical world—building concentration, emotional regulation, and a sense of purpose.

Montessori materials aren’t “toys”—they’re precisely designed learning tools. A golden bead chain teaches the decimal system; pink cubes teach volume and sequencing. These concrete objects prepare children for abstract thinking by grounding concepts in physical experience.

Psychologists like Dr. Angeline Lillard have found that children in Montessori classrooms outperform their peers in academic, social, and executive functioning measures. One peer-reviewed study even showed that Montessori students had better reading and math scores without formal testing or grading.

The Spiritual Side of Maria Montessori

Though rooted in science, Maria Montessori’s work had a deeply spiritual component. She viewed the child as a force of peace and potential renewal for the world. During her years in India (1939–1946), she worked closely with spiritual leaders, including Mahatma Gandhi, and introduced the concept of “Cosmic Education.”

This stage of her philosophy invited children to see themselves as part of a larger universe—to explore not just science and math, but moral questions, human interconnectedness, and environmental stewardship. It was education for the whole person, not just the intellect.

Montessori’s lectures on cosmic education are preserved in the AMI archives.

Empowerment Through Education

Maria Montessori didn’t just educate children—she educated women. Her training programs welcomed female teachers at a time when professional opportunities for women were scarce. Her schools empowered young girls to think critically, lead, and explore interests beyond domestic roles.

Her feminism was not just theoretical. As one of Italy’s first female doctors, Montessori faced discrimination and harassment from her peers. But she never allowed societal norms to determine her path. Her life modeled the very independence she sought to instill in children.

Montessori and Children with Special Needs

One of the least acknowledged contributions of Maria Montessori was her early advocacy for children with disabilities. Long before inclusive education became policy, Montessori championed the idea that all children have the potential to learn and flourish.

Her sensory materials were originally developed for neurodivergent children. She believed that instead of separating them, educators should adapt the environment to accommodate different learning styles. Today, many therapists, occupational specialists, and special education programs incorporate her principles in supporting children with autism, ADHD, or sensory integration challenges.

Learn more at The Child Mind Institute on how Montessori methods help children with learning differences.

Maria Montessori’s Final Years

Even in her later years, Maria Montessori continued to teach, speak, and write. She was nominated three times for the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1952, at the age of 81, she died in the Netherlands, leaving behind not just a method, but a movement.

Her epitaph reads: “I beg the dear all-powerful children to unite with me for the building of peace in man and in the world.”

This final message summarizes her lifelong mission: not only to educate minds but to elevate humanity.

FAQ

Who was Maria Montessori and why is she important?

She was an Italian physician and educator who created the Montessori method, transforming how children are taught and respected.

What are the main principles of Montessori education?

Key ideas include child-led learning, a prepared environment, mixed-age classrooms, and developmentally appropriate materials.

Are Montessori schools only for privileged children?

No. While many private Montessori schools exist, public programs and low-income initiatives make the method increasingly accessible.

How is discipline handled in a Montessori classroom?

Through freedom within structure—children learn self-discipline by making choices and experiencing natural consequences.

Is the Montessori method scientifically supported?

Yes. Decades of research show benefits in cognitive, emotional, and social development, often outperforming traditional models.